Reading Time: 8 Minutes

Our Obsession with Righteousness

Almost everyone who observes their mind in a disciplined manner finds it impossible to stop it from spontaneously creating judgments. Meditators who try tend to describe the following pattern: One first condemns judgments as “bad”. Then one condemns oneself as “bad” for having them. Over time it becomes clear “that judging the judging” is not helpful, as efforts to stop the mind from judging do nothing to alter the mind’s propensity to judge. Only the focus of one’s judgments changes, such that the mind itself becomes the target.

Appreciating the degree to which the mind is preoccupied with moral judgment does not necessarily require methodical observation. A quick glance at the content of social media platforms reveals a proclivity for moral judgment that cannot be ascribed to individual idiosyncrasy but that is rather reflective of an obsession with righteousness representative of the normal human condition.

The Conditions that Molded Righteous Minds

The human proclivity for righteousness can be informed by an awareness of the conditions in which it originated and proliferated. Evolutionary theory seeks to understand the human mind as a device for survival and reproduction and sees righteousness as one of its various techniques. To approach the human proclivity for moral judgement from an evolutionary perspective is to inquire how the tendency promoted the survival of individuals and groups who possessed it. 1

Homo sapiens probably began communicating judgments about what is “good” and “bad” – about how groups should be organized to promote survival and address threats – about 100,000 years ago.2 In the ever-changing environments through which the species expanded, those groups that began to extensively cooperate with one another survived. When individuals went scavenging, hunting, or gathering, for example, they would do so in teams. When an individual or small group found a good cache of food, it was brought back to the band and shared with them. While this form of social cooperation wasn’t always in the best short-term interest of the individual, it would be invaluable to the group, such that those groups that cooperated more tended to be the ones that survived to leave more descendants. The fact that the world is now inhabited by about 8 billion Homo sapiens – and only about 1 ½ million primates – is attributable to this capacity for cooperation: Whereas primates relentlessly compete against each other, humans are the most cooperative species (among primates) by far. Like the development of speech and language, the proclivity for moral judgment evolved because the capacity for cooperation that that it facilitated proved enormously adaptive to those individuals and groups in whom it manifested.3

People tend to regard their judgments about what is “right” and “wrong” as having nothing to do with utility. Individuals may even pride themselves on trying to “do what is right” when it would seem expedient to do otherwise. The fact that the functional aspects of morality are often invisible to the individual is, ironically, reflective of morality’s social function. An individual’s belief in the absolute value of her moral judgments reflects the salience of the social brain and the fact that human minds evolved under conditions where keeping groups together was a matter of life and death.

Morality as Cooperation

While the social function of morality tends to be invisible to the individual, social scientists approach morality as a mental module that is virtually synonymous with cooperation. Those who develop the Moral Foundations Theory (initially proposed by Jonathan Haidt) refer to this approach as Morality-as-Cooperation and characterize morality as a collection of biological and cultural solutions to the problems of cooperation recurrent in human social life. These biological and cultural mechanisms provide the criteria by which the behavior of others is judged. This collection of cooperative traits—instincts, intuitions, and institutions— are called morality.

Groups share judgements pertaining to ideas, behaviors, and practices. Those deemed acceptable by the group are called norms. Values are the standards employed to determine whether a practice is judged “good” or “bad”. An ideology is a system of beliefs informed by values that relates to how the group should be organized and how work should get done. Norms, values, and ideology are essential group functions, and the extent to which they are shared will exercise a determining influence on whether the group will survive.

Although the content of moral systems – behaviors deemed “good” or “bad” – vary enormously from culture to culture, every human culture that has been present for the past 40,000 years has probably been equipped with a moral system. Very large groups – such as the modern nation-state – evolved only within the last several hundred years and necessitated moral systems shared by millions of individuals.

Moral Aggression

If the moral systems that hold groups together are not maintained and defended, the group will cease to exist. “Moral Aggression” is one of seven categories of aggression that can be defined in any human group, and, like other forms of aggression, is a pattern of behavior that evolved to counter threats. Whereas some forms of aggression are employed by groups to defend territory, kill prey, or defend against predators, moralistic and disciplinary aggression is used to enforce the rules of society. 4

While the expression of moral aggression that currently pervades American society – “cancelling”, “kicking off” perceived enemies from social media, and “doxing” – are new to the extent that they employ digital technology, in an important sense such behaviors are older than civilization itself, insofar as they function as a means of maintaining group solidarity and defending one’s group from the real or perceived attacks of others.

If moral aggression is vital to the defense of the human group and can be found in any human group, and if digital technology is simply a new means by which this ancient form of aggression is expressed, how are current trends in the expression of moral aggression problematic to mental health and functioning?

Group Identification

Cultural norms increasingly encourage individuals to identify with those who are perceived as manifesting an aspect of physical appearance (e.g., skin color) that is deemed salient. Ideologies that justify the sense that a specific aspect of an individual’s appearance is the sole determinant of the group to which one belongs, one’s social position, and one’s interests – so called “identitarian” ideologies – are increasingly prevalent. Because identitarian ideology views social problems through the prism of race, ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation and explains social reality with reference to these constructs, it can foster a sense of disaffiliation among individuals who do not manifest the “same” physical appearance or orientation. The basic sense that “we are all in this together” is disrupted when individuals in pluralistic nation-states become convinced that their interests and prospects exclusively correspond to the group with which they identify. 5

Ideological Tribalism

These shifting identifications create sub-groups within organizations, institutions, and nations. Ideologies that justify the idea that an individual’s interests exclusively align with their “identity” has contributed to the development of “ideological tribes”.

Moral aggression is increasingly employed as a means of disciplining and enforcing rules within ideological tribes and as a means of warring with those who are perceived as opposing the tribe’s interests. Individuals within each tribe gain status by enforcing moral discipline toward members who are seen as wayward and by doing battle with the opposing ideological tribe. 6 This moral aggression gives rise to “culture wars” that disrupt the functional units (i.e., organizations, institutions, and nation states) within which people work and upon which the continued functioning of society depends.

Impaired Reality Contact

An inherently problematic aspect of ideology is implied by its definition: the term “ideological” is used to refer to something that relates to “an idea or ideas, especially of a visionary kind” (OED). Ideology, by definition, consists of ideas and opinions, not facts. Because ideology concerns itself with the way things should be and employs values and opinions to assess the way things are, the ideological mind is always at risk for impaired contact with reality. In other words, ideology not only “binds” the ideologue to those who adhere to the same ideology, it also “blinds” him to aspects of reality that his ideology ignores.7

One aspect of this problem is attentional. The ideologue scans and selects for experiences that justify and support the ideology to which she is attached. A person who describes herself as “progressive”, for example, is prone to find evidence of injustice when searching for the basis of social problems. A self-described “conservative”, on other hand, is likely to find evidence that social problems are attributable to insufficient respect for legitimate authority. “Conservatives” historically scanned reality for evidence that social problems are rooted in an insufficient sense of individual responsibility and inadequate feelings of loyalty to sacred institutions such as family, church, or nation. More recently, self-described conservatives focus on finding evidence that collective action threatens individual liberty.

The ideological diversity perpetuated by such attentional mechanisms does not necessarily culminate in a functionally impairing loss of reality contact. Groups benefit when adherents to diverse ideologies champion values to which they selectively attend and when adherents to different ideologies cooperate and compromise with one another by addressing facts and values appreciated by different ideologues. A self-described “progressive” might focus on facts that reflect injustice, for example, while a self-described “conservative” might focus on perceived threats to individual liberty. Neither ideologue has lost contact with reality – only different aspects of reality are emphasized – and cooperation and collaboration can occur between ideologues.

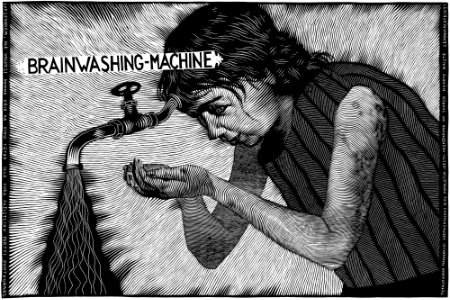

Loss of reality contact occurs when ideologues not only do not attend to facts that relate to values cherished by an opposing ideology but when they are unexposed to facts necessary to understand the way things really are. This can occur when intermediaries (i.e., “media” channels) to which ideologues are exclusively exposed elaborate narratives that not only ignore salient aspects of reality but treat facts necessary to understand the way things really are as if they are opinions or enemy propaganda. The strategy that organized groups use to sow loss of reality contact is not complicated: loss of reality contact can be induced in millions of individuals by simply repeating the same false information or narrative. 8

References:

1. Wilson, E.O. On Human Nature. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. 1978. Page 2.

2. Lent, Jeremy. The Patterning Instinct. Prometheus. 2017.

3. Haidt, Jonathan. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion. Vintage. New York. 2012.6

4. Wilson, E.O. On Human Nature. Harvard University Press. Cambridge,

Massachusetts. 1978.

5. Voorspoels, W. Bartlema, A., Wolf V. “Can Race Really be Erased: A Pre-Registered Replication Study”. Front. Psychology, 16 September 2014.

Volume 5 – 2014. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01035. This study replicates findings by Kurzban et al (2001) by demonstrating that when cues of coalitional affiliation do not track to race, subjects markedly reduce the extent to which they categorize others by race and may cease doing so entirely.

6. Fiske, Alan Page and Tage Shakti Rai. Virtuous Violence. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

7. Haidt, Jonathan. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion. Vintage. New York. 2012.

8. “Tactics of Disinformation”

https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/tactics-of-disinformation_508.pdf\